Poet – Writer – Editor

Stories

Ginsberg Lives

The funeral started at 9:00 and I couldn’t get there until 10:30 at the earliest. My buddies Eliot and Andy doubted I’d get in because the funeral was supposed to be for Ginzy’s very closest friends and family, but the Post and Daily News had printed the address of where the service was to be held. I figured if I didn’t get in, so be it, I’d stand outside with all the other grieving souls. It was at the Shamballa Center on 22nd Street and was to be a Buddhist service. I had no idea what to expect.

Why was I going to Allen Ginsberg’s funeral? Because he was a friend, simple as that. He had been a friend for twenty years, definitely not the most exciting twenty years of his life, but twenty years that were virtually my entire adult life. Eliot Katz and I first met Allen in the fall of 1976. Of course, I’d heard of Allen Ginsberg before that. I’d seen him on the t.v. news chanting, marching, dancing, playing his strange black harmonium, exclaiming his poetry at various demonstrations, be-ins and happenings throughout my childhood in the sixties. In sixth grade I put a poster of him up in my room, not for any literary significance, but because he looked so cool and so strange with all that hair coming out of the stars and stripes of his Uncle Sam hat. I read about him in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test which was like my Bible during my high school druggy days. As a matter of fact, I still have the book. Here’s what Wolfe wrote about Ginsberg’s encounter with The Hells Angels: “Ginsberg really bowled the angels over. He was a lot of things the angels hated, a Jew, an intellectual, a New Yorker, but he was too much, he was the greatest straightest unstraight guy they had ever met” (154).

I read the poem Howl during my freshman year of college. Howl was a poem that did what no other poem could do; it spoke to me directly from the page. No interpreters were needed. In a matter of months, I was transformed from a biology major future doctor of America to a black clad too much attitude for so small a frame English major who wanted to some day be a famous writer. Also, during our freshman year at Rutgers, Eliot and I took an English class called The Beat Tradition in American Literature. It was taught by the most popular teaching assistant at the school, Bob Campbell, or Beat Bob Campbell as he was sometimes known. This class was like no other class I ever had taken. Each class session a different student would bring in a jug of wine for us to share as we debated the finer points of the Beat Generation. After a few weeks of wine fueled discussions, someone lit up a joint, and from that moment on pot smoking became an added stimulant to our daily discussions. We would stuff our denim jackets under the door so that the smoke would not waft into the hallway and the other classrooms. It was during these heady days of our “Beat Trad” class that I decided to embark on the career path of becoming a beatnik poet.

One fall day of our sophomore year Eliot and I were drinking beer on the front steps of our new apartment dumbly watching the Puerto Rican kids play kickball in the street. A black taxi pulled up in front of our house. A bald, bearded, slightly stooped man got out and began unloading boxes from the cab. It was Ginsberg! We got off our asses and helped Allen Ginsberg carry the boxes which were filled with copies of his father’s book of poems to the house across the street which was the home of Kevin Hayes. Kevin was about five years older than us and the only real poet we knew. He was also the president of the Rutgers Gay Alliance, the group that was sponsoring Allen Ginsberg’s poetry reading that night. We unloaded the books and promised Allen and Kevin that we would see the reading that night.

The poetry reading was more like a concert than a literary event. Ginsberg had a rock star aura about him, drawing the audience to his words, making the audience of about 500 people feel as if he were addressing each person individually. When it was over, people lit matches and lighters, and the star poet recited an encore and then another. After the encores were finished, I waited in line to talk to Allen Ginsberg and to give him a poem I had written that was inspired by his poem America. My masterpiece was entitled America 1976 and it was a godawful mishmash of teen angst, unrequited love, faux street wisdom, drug induced paranoia and recycled KISS lyrics. Ginsberg looked at the poem for about thirty seconds and said “The problem with this. . .” I cut him off. “Allen,” I said, “put it away and read my poem when you have the time, then write me and tell me what you think. My address is on the back.” What can I say, I was young, brash and stupid.

Eliot and I drove Allen back to his apartment in the city that night in Eliot’s orange Chevy Vega, I guess because nobody else had a car, and maybe because he liked the idea of being driven home by two 19-year-old boys. We received a free guided tour of the East Village with Allen merrily playing tour guide and pointing out the historical significance of such non-sights as the Gem Spa, The Holiday Cocktail Lounge, and the apartment where Leon Trotsky lived before he went off to Mexico to meet his fate. We helped him carry his boxes of books up the flights of stairs to his apartment on East 12th Street. Allen asked us to sit down and join him for a cup of tea. I visually took in the landscape of his apartment thinking so this is what the life of a poet looks like.

About ten days after our meeting I received a postcard. It’s packed away in a box now, but it said something like this: “. . . to prevent falling into the dumb singleminded trap you fall into you must be mindful that each line should ring with poetry, imagery, panoramic vision, wordplay. As New Jersey bard William C. Williams states, ‘No ideas but in things.’ Your poem has moments, perhaps it could make a good Haiku. . . With Love, A. Ginsberg.” At first, I was hurt, then I was angry, but when I thought about it, I was honored that a world famous poet and beatnik would take the time out of his schedule to spend on me.

Over the years Allen Ginsberg and I maintained a friendship. A friendship that has had its ups and downs but lasted. Because of him and with him I read my poetry to larger crowds than I ever again could hope to draw. Allen once did a reading with Eliot and I at the Rutgers Student Center where he split the door with us 50/50, which was enough money for us to start our own magazine which we titled Long Shot. Allen has been a frequent contributor to our magazine, giving us previously unpublished poems and photos and never asking for anything in return. Many of the friends I have today are friends I met because of Allen Ginsberg. The poems I’ve written often have Mr. Ginsberg in mind as the audience, whether to impress him or defy him. Some poet once said “when a man dies, a universe dies with him.” He probably meant that each person has an almost infinite amount of associations and memories and feelings and thoughts within him or herself and when that person ceases to be alive those connections are lost. Allen Ginsberg’s death must have left a sizable hole in the universe.

The last time I saw Allen was about three months ago at a memorial poetry reading for Herbert Hunke. After the reading, Allen and I were going to share a cab to the Port Authority, he to catch a bus to Paterson to visit his stepmother, and me to catch a bus home to Hoboken. Eliot offered to drive Allen to the Port Authority and me home. We had a laughter filled drive across town at the expense of a mutual friend who had asked Allen if he’d listened to the compilation he produced of golf songs. Allen didn’t understand the concept — songs about golf??? We spent the ride goofing on possible golf songs such as, “I’m Your Bogeyman,” “Get Down and Bogey,” “Take This Club and Shove It,” “Putt, Putt, Putting On Heaven’s Door.” Somehow the conversation got around to death. “When my time comes,” Allen said, “I want my body to lie in state at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and I want all the lovers I’ve ever had who are still around to file past my coffin.” “Hello Allen” I said, “first of all you’re a Jew, and second of all you’re a homosexual. Cardinal O’Connor’s not going to let you have a funeral in his cathedral.” He looked thoughtful for a moment, “Maybe then, St John The Divine. They’re pretty liberal.” We laughed.

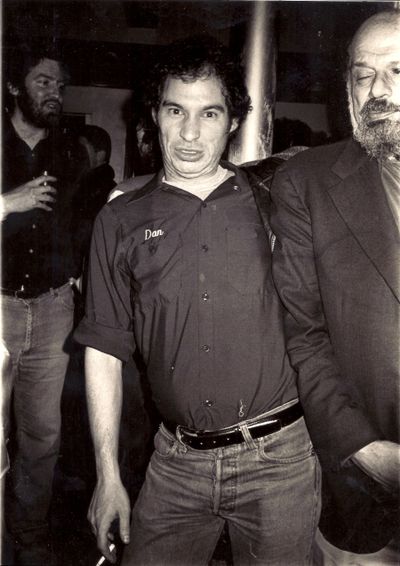

Of course the funeral is packed. Over 500 people sitting on square red and yellow cushions listening to Buddhist monks chant. For his family and for all the Jews, The Mourner’s Kaddish. Five hundred of Allen’s closest friends in New York. People whose lives he touched in friendship. People who have stories to tell. There’s Peter Orlovsky. There’s Allen’s 95-year-old stepmother. There’s his brother Eugene. There’s Amiri and Amina Baraka. There’s Gregory Corso. There’s Hettie Jones. Patti Smith. Anne Waldman. Lou Reed. Natalie Merchant. Phillip Glass. Laurie Anderson. David Greenberg. Hersch Silverman. Andy Clausen. Eliot Katz. And Me.

originally published in Long Shot 20, 1998